What does stress tell us?

April is Stress Awareness Month but what is stress? The Head of Mental health Education at Suffolk Mind, Ezra Hewing tells us more…

Mental health is a spectrum…

The way we see mental health has changed. Thanks in part to celebrities being more open about their mental health, we feel better able to talk about our mental too. All of us have mental health and our mental health can fluctuate too – depending in part on how we respond to stress.

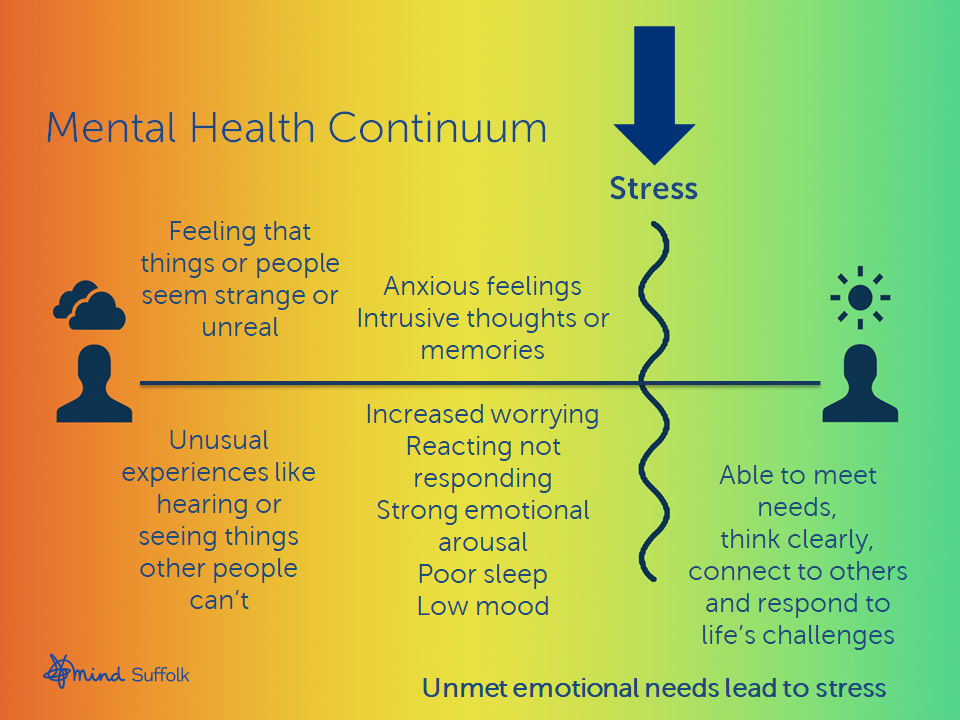

While we might sometimes think about mental health in terms of conditions like depression, anxiety and more serious conditions, most professionals agree that our mental health is on a continuum, or a spectrum. Most of us will spend the greater part of our lives at the wellbeing end of that spectrum, while a few will experience serious mental ill health at the other end.

Wherever we are on the mental health continuum, it’s important to understand that stress is the crossover point. If we don’t address stress, it can give rise to low mood or trigger more serious conditions.

What does stress tell us?

An important thing to understand is that stress is nature’s way of telling us that a key emotional need is not being met in our lives.

Our emotional needs include the need to feel safe; to feel a sense of control over our lives; to feel that we have a status which is respected by others; to give and receive attention; to feel part of the wider community; to have privacy and downtime to reflect and make sense of our lives; to feel that we share an emotional connection with at least one other person – or a pet!; and to feel that we are stretched in ways which give our lives meaning in purpose.

Now when our lives are busy and we are juggling work and family life, it’s easy to lose sight of how our emotional needs are being met. Just the thought of addressing parts if our lives we are not completely satisfied with can seem stressful in itself, so what can we do?

An important first step might be to create just ten minutes in your day where you will be free from interruptions and distractions. If you can’t do this at work or at home, you might be able to find a quiet place in a park, or even just sitting in your car. Just doing this for ten minutes each day to meet the need for privacy can be the first step to reducing stress.

It’s easier to think clearly when we are calmer, so doing something to relax is important. You might like to try the following breathing exercise to calm down and lower your stress levels:

- Start by placing your hands on your stomach and breathe in filling your stomach up with air and hold it (many of us tend to shallow breathe most of the time).

- Then breathe out more slowly than when you were breathing in. It is the out-breath which stimulates the relaxation response.

- Repeat this process, counting to 7 in your mind when breathing in, and to 11 when breathing out. The number doesn’t really matter so long as the out-breath is longer than the in-breath!

Try doing this for ten minutes a day and, when you’re feeling calmer, think about which emotional need you will address first. Perhaps you’ll plan to spend time with people you share a connection with. Perhaps you’ll reflect on the areas of your life you can influence and take control of. Maybe you’ll put some time aside to practice a skill you’ve neglected for a while, just to remind yourself of the things you are good at. Or you could arrange to go for a walk with a friend to remind yourself of what it feels like to be free of stress for a time.